The late painter Manoucher Yektai of Sagaponack was widely recognized as having all the towering talent — and unabashed hubris — requisite in a great artist. So why has he not been recognized among the legends of his generation?

By Biddle Duke

Manoucher Yektai was stubborn about his aspirations.

From an early age he believed he possessed something of significance, something the world needed. He spoke of that belief all his life. It drove him as a youthful poet and inexperienced painter from tradition-bound Iran in the 1940s, and continued to animate him and provide powerful direction as he navigated the art worlds of Paris, New York, and eastern Long Island. His whole life was an endeavor to meet his colossal self-imposed expectations, and he presented no shortage of hubris when it came to his ability to do so.

“I am a great artist,” he frequently told those closest to him. Boastful though the words may sound, usually delivered flatly, as a simple fact, his audiences in these moments didn’t necessarily see it as exaggeration. It was unquestionable and long established: Yektai possessed immense talent.

To reach such heights, he was purposeful, sometimes to the point of obsession, enabling him to devote himself fully to his work in a way that many people cannot.

When Yektai died on November 19, 2019 at his home in Sagaponack, his life had been rewarded with recognition, wealth, and, for a little more than a decade around the middle of the last century, significant artistic fame. To any outside observer he had been a success in most of the conventional ways, and in the intangible ones, too: He had met the world’s beauty with his own.

Still Life with Cantaloupe, 1976, oil on canvas, 52 X 56 inches

“Manoucher was an atheist,” the Iranian writer Alimorad Fadaienia said. “But he found the hand of God in everything. He saw the good in everything. An apple was as important as a human being. That is how he painted.”

But Yektai did not in his lifetime reach the peak that he had sought. His name is not cited among the great 20th-century painters. Important museums, the Museum of Modern Art, for example, purchased his paintings, but none assembled a collection. When Yektai’s work comes up for sale, the prices are significant but well below other noted artists of his era. Most important, when we look up at the galaxy of great artists, do we find Manoucher Yektai’s star?

If his family has their way, the answer to that question will be yes. Working with the Karma Gallery in Manhattan’s East Village and the Wainscott and Manhattan-based art consultant Rob Teeters, Yektai’s wife and two sons — Niki, Nico, and Darius — have launched a celebration of his life and work. It began with a retrospective exhibition of Yektai’s work at Karma in October, and will be followed by a book, published by Karma this month, of his paintings, accompanied by his life story and essays exploring the trajectory and significance of his art by a young Iranian artist and two art writers. A key thrust of all this will be to exhibit Yektai’s many late-in-life paintings, almost none of which have been seen publicly.

If Yektai is supposed to be up there with Cezanne, Bonnard, Picasso and his friend de Kooning, what happened?

“He was a great painter,” said the gallerist Alex Rosenberg, who represented Yektai in the 1980s, “who did everything he could not to be one.”

Rosenberg, whose century-long life span in the art world mirrored Yektai’s, empathizes with the artist’s angst: “He deserved every accolade. His talent was huge. But he was a very rebellious person in a very quiet fashion.”

Yektai was born in 1921 into a family of some means, owners of several buildings with storefronts on the first floor and apartments above, on a busy street in Tehran. From an early age, he wrote poetry, and by his teenage years was getting published in Iranian journals and newspapers. Through a painter friend he discovered European masters and contemporary artists — Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, Bonnard, Monet, Renoir. It is difficult to imagine from the perspective of today, where everything is at our fingertips, but access to Western art images was limited in Tehran in the 1930s, and it was only in his late teens that he was exposed to the brilliant colors, the brilliant use of abstraction, the inherent emotion of contemporary painting. It thrilled Yektai.

Poetry, he concluded, had its place, but it was constrained by language. The emotion and beauty conveyed in paintings is universal, he declared to his family, and overnight he resolved to be a painter and to study in the West. In his early 20s he left Iran, studying for a year in Paris before settling in New York.

Yektai’s arrival in the United States couldn’t have come at a better moment. It was the late 1940s. The West had defeated the Nazis and the Japanese, and America had emerged as a global superpower. Untethered from the war effort, he found a nation surging with energy and optimism, its art world exploding with exhilarating, wild abstraction. His own work at the time — in full evolution but predominantly still-lifes, landscapes, and portraits executed in big, bright, lush brushstrokes — was for almost two decades powerfully in sync with the new American ideal, even as it was rooted in rich European sensibilities and Persian traditions.

Not long after his arrival in New York, Yektai was embraced as an emerging Abstract Expressionist and occasionally cited at the time as among the movement’s early founders. He gently dismissed the designation, but in many respects the art world spotlight turned on him because of this inclusion.

Extraordinary praise from critics and fellow artists, including his more celebrated contemporaries, followed. He was lauded as an “artist’s artist.”

“Either this is an animal becoming a man or a man becoming a God,” Landės Lewitin reportedly commented to Mark Rothko, cryptically, after seeing Yektai’s early works at a solo exhibition in the 1950s at the Poindexter Gallery in New York City, where many of the great Abstract Expressionists were represented.

“Yektai,” the poet John Ashbery wrote in 1961 in the French magazine Aujourd’hui: Art et Architecture “wants to render us conscious of our existence from second to second, of the joy of breathing, of the rapid changes of things.”

“You could say his success was almost accidental: His timing was perfect,” his son Nico said of his father’s quick rise.

But in the late 1970s, Yektai fell out of favor in the quickly evolving art scene. His work, in many ways classical, seemed out of touch. And, after more than a decade of declining sales, Yektai deliberately stepped away from the commercial art world, an isolation that was made possible in part thanks to his marriage to Niki Kulukundis, a member of a Greek shipping family.

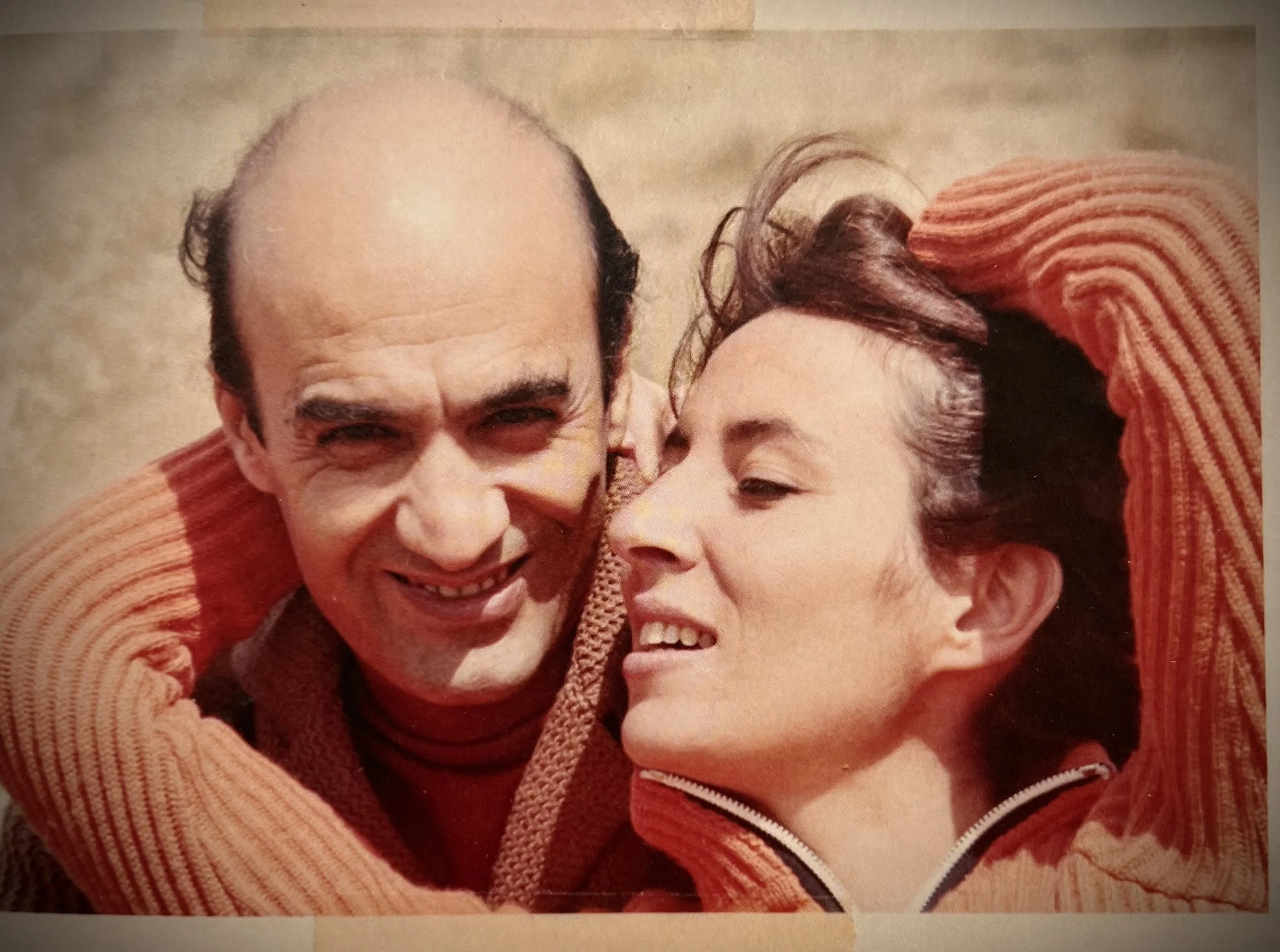

Yektai with Niki. Photo: Courtesy of the Yektai family

Yektai certainly could have continued to swim with the art current. But he was stubborn and defiant. He didn’t want the art world if it did not want him.

“Manoucher certainly was arrogant. It was all about him,” Niki, his widowed wife of five decades, said in an interview early this year. This description could be seen as unkind, but Niki offers it with tender admiration. “He never complained about his lack of recognition. He just absolutely never did anything about it. He just worked..”

Yektai’s isolation extended — with a few notable exceptions — until his death in 2019. Yet that period of more than four decades was joyful and productive. The couple raised a family together. And, forever disciplined about making art, Yektai produced an immense volume of work, marking a stunning and largely unrecognized peak in his creative life.

“It’s his best work,” his son Darius declared. “He’d come fully into his own. He was a poet, and the paintings he created in the last part of his life are his most poetic.”

Yektai’s Persian soul also emerged powerfully in his work in the final third of his life. Bright pots of flowers, moody landscapes, portraits of people he loved; celebrations of rural and everyday scenes; the bowls of fruit so common in traditional Persian households; his use of color and patterns — the paintings he produced during his last decades are brusque and masculine even as they are tender and reflective. They burst with color. Some might think it a stretch to see anything distinctly Persian in any of this, but those who knew him recognize his ancestral roots there.

For most of his life — three-quarters of a century — Yektai lived, worked, and raised a family in the United States, but he was never American.

“He was inspired by America, and he came here for that inspiration, but his soul was completely Persian,” Niki said.

“The way he did his paintings is the way he did his poetry,” his friend Alimorad Fadaienia observed. “The roots of it are Iran: The reds are the reds of Isfahan, the blues of the tiles we see everywhere in Iran.”

“Inherent in his painting he retained his Persian heritage,” said Donna Stein, the art historian who curated a Yektai retrospective at Guild Hall in 1998. “He depicted ideas with a different scale and intensity as if he were blowing up little units of Persian miniatures.”

Manoucher Yektai is beloved as a poet in Iran. His poems have been made into plays, and his place in the Iranian psyche is as secure as a poet as it is as a painter. Likewise, his exodus to and success in the West have been an inspiration to Iranian painters who followed.

His life and experience prove what many in the art world know to be true: that achieving widespread, sustained fame requires more than just making stunning paintings. One must play the game. He anticipated greatness but refused to do what was expected of him to achieve it while he was alive; he was stubbornly unwilling to swim in the art-world slipstream, and had the financial means to make that choice.

“He simply did not reach out to collectors or galleries,” Niki said. “It was pride, shyness. He wasn’t interested in any of that. He just would not promote himself. And, if it wasn’t for me, he wouldn’t have socialized.”

Will Yektai’s work ultimately achieve greater recognition? We know his short answer to that question. But he also would say that his ascent is likely to take hundreds of years. An eternity — but, to him, great art transcended the figment, the construct, of time.

Yektai would often remind his children that his favorite poet, the hugely popular Persian mystic Rumi, was for centuries known to relatively few. Rumi became a household name only when his poems appeared in English translations in the early 1900s, six centuries after his death. So, Yektai would say, “I am on the 600-year plan.”

“You can’t destroy great work,” he would tell his sons. “It will be here until the world gets it.”

—

This article is taken from the biographical chapters in by Biddle Duke in “Manoucher Yektai” published by Karma Books, N.Y. www.bookstore.karmakarma.org/product/manoucher-yektai/

Duke is a contributing editor to East.